By Colin G. F. Thomas

Choosing

the

subject of the Durotriges is perhaps

a little ambitious. However, the coins of these pre-Celtic tribes do

hold a

certain fascination. These coins cannot be dated to any recognized time

scale,

at least not accurately, but a period of mid 1st Century BC

to mid 1st

Century AD seems to be common. Unfortunately a more defined dating

period is

not, at this stage, possible.

Choosing

the

subject of the Durotriges is perhaps

a little ambitious. However, the coins of these pre-Celtic tribes do

hold a

certain fascination. These coins cannot be dated to any recognized time

scale,

at least not accurately, but a period of mid 1st Century BC

to mid 1st

Century AD seems to be common. Unfortunately a more defined dating

period is

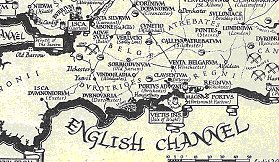

not, at this stage, possible. The

Durotriges people are steeped in

mystery even though it is known that they existed and also known where

they

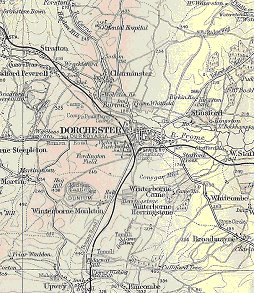

resided. The county of Dorset in southern England and the western part

of

Wiltshire and eastern part of Somerset seem to have been the boundaries

of

these people, with their main centre situated in what is now known as

Dorchester.

The

Durotriges people are steeped in

mystery even though it is known that they existed and also known where

they

resided. The county of Dorset in southern England and the western part

of

Wiltshire and eastern part of Somerset seem to have been the boundaries

of

these people, with their main centre situated in what is now known as

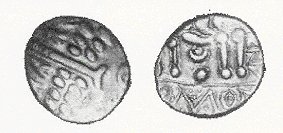

Dorchester. Coins

of the Durotriges have no known text

on them nor do they represent figures of human beings and this makes it

all the

more difficult for the numismatist to identify and catalogue. One

aspect

however is quite common on the said coinage. A stylized disjointed

horse figure

usually, but not always, appears on the reverse of a great number of

coins. Of

course other Celtic coinage depicts such figures but the Durotrigan

coinage appears to be of a cruder manufacture. Many are

struck in debased silver – billon staters – but gold and silver coins

do exist.

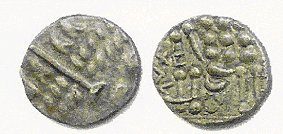

Coins

of the Durotriges have no known text

on them nor do they represent figures of human beings and this makes it

all the

more difficult for the numismatist to identify and catalogue. One

aspect

however is quite common on the said coinage. A stylized disjointed

horse figure

usually, but not always, appears on the reverse of a great number of

coins. Of

course other Celtic coinage depicts such figures but the Durotrigan

coinage appears to be of a cruder manufacture. Many are

struck in debased silver – billon staters – but gold and silver coins

do exist. Maiden

Castle, Britain’s largest hillfort, was built prior to the period of

occupation

of the Durotriges, but was manned by

them as a major centre of activity. Today, over 2,000 years later, the

fort

still stands as a testament to the abilities of those people. It covers

a vast

area with terraced levels and moats guarding the apex of the structure.

It

would have been a very easy place to defend and indeed battles have

been fought

there.

Maiden

Castle, Britain’s largest hillfort, was built prior to the period of

occupation

of the Durotriges, but was manned by

them as a major centre of activity. Today, over 2,000 years later, the

fort

still stands as a testament to the abilities of those people. It covers

a vast

area with terraced levels and moats guarding the apex of the structure.

It

would have been a very easy place to defend and indeed battles have

been fought

there.Excavation in recent times has revealed burial sites in the vicinity where warriors had fallen in battle.

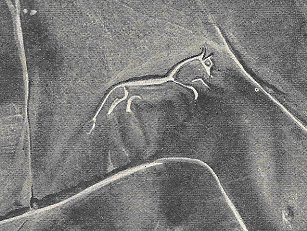

With

this in mind, one can only speculate about the origins of the hillside

horse of

Uffington in Berkshire. This massive carving, similar in design to the

coinage

as mentioned, stretches an incredible 114 metres by 40 metres high and

must

have had some significance to those who painstakingly made it. Perhaps

the

horse was an indication that religious ceremonies had taken place.

With

this in mind, one can only speculate about the origins of the hillside

horse of

Uffington in Berkshire. This massive carving, similar in design to the

coinage

as mentioned, stretches an incredible 114 metres by 40 metres high and

must

have had some significance to those who painstakingly made it. Perhaps

the

horse was an indication that religious ceremonies had taken place.Do the marks on these coins represent a counting mechanism or the recording of some event or do they reflect a division of the year or the seasons? Does the disjointed horse depict a deity, something to be revered or worshipped? Could the button forms show a harvest where harvest might refer to wealth? And the ears of wheat may count for a healthy cache of food, again meaning wealth. This, of course, is just speculation but it is interesting to imagine that the meaning of the symbols on these coins stand for something vital to the people who produced them. Could these people have copied signs from the night sky and what value was put on these coins one might inquire.

Photo Courtesy of Brian Beresford of the Havering Numismatic Society, England

Photo

Courtesy of Mike

R.Vosper

Photo

Courtesy of Mike

R.Vosper Photo

Courtesy of Mike R.

Vosper

Photo

Courtesy of Mike R.

Vosper Photo

Courtesy of Mike R. Vosper.

Photo

Courtesy of Mike R. Vosper.As previously stated, to fully understand the Durotriges people more study needs to be undertaken. Precious little information is evident and the coinage, as in many cases throughout history, could be a major factor in delving into the lives of these people. It is known that apart from a mint established at Hengistbury Head, a well established trading centre existed. Merchandise arriving from Europe by boat supplied various commodities not available locally. It was by no means a one way trade as pottery, mentioned previously, could be exchanged for items needed. To date, and I stand to be corrected on this statement, no Durotrigan coinage has been found outside the immediate area occupied by these people. There are, to date, no reports of this distinctive coinage having been found in Europe. Did money exchange hands for these commodities or was barter the media used in transactions ? It would appear that the said coinage remained in England and was used purely in the Dorset area. And this is rather surprising considering that the Uffington horse, earlier mentioned, could have been the inspiration for the disjointed horse design on coinage. Certainly the effigy carved on the hillside in Berkshire was done long before the Durotriges established themselves in the Dorset area. Speculatively, was this horse seen by these people and copied on to the coinage and who were the mint masters of the time ? The coinage leaves us with more questions than answers.

The Uffington Horse in Berkshire

This picture was taken c 1938 and

the figure has undergone certain chnages since that date

Hill

Forts Maiden Castle

Hod Hill

Poundbury Rawlsbury

Eggardon Spetisbury

Abbotsbury

Badbury Pilsdon Pen

Banbury South Cadbury

Hambledon Hill Battlesbury

Note:- The main horde of coins found were discovered at Badbury, Hod

Hill, Maiden Castle and south of the city of DForchester, and on the

Isle of Weight. Over 800 coins were unearthed at Badbury

Weapons Animal Bones

It

is perhaps sad that bodies of these people, other than skelatal remains

that is, have not been unearthed. How much more would researchers

have learned

had

figures similar to those of Tollund Fen Man, Grauballe Man, Lindow Man

or

Elling Woman been discovered. These

bodies were well preserved and date back to the time of the Durotriges

people.

Carbon dating has placed these incredible finds between the years

290BCE and 119CE,

the precise time span pre-mentioned. Re-construction of facial features

of some

of these bodies has created for the historian and student alike a focal

point

by which real interaction between the past and present can intermingle.

To understand

that these people actually walked this earth over 2000 years ago is a

sobering

thought and the Durotriges people are no exception to this scientific

observation. What was it like to live in those times ? How did they

feel about

one another ? What was their everyday lives like, what were their

worries and

issues of the day ? How did they interact with neighbouring tribes ?

Was health

an issue and at what age was it considered to be old ? Certainly those

skeletons that have been found were not old by today’s standards,

arguably 35

to 40 years at most when in the 21st century one can expect

to

double that figure.

The Search for the Durotriges” by Martin Papworth

‘Romantic Britain’ by

Tom

Stephenson

‘The Celts’ by Peter

Berresford-Ellis

‘Written in Bones’

edited by

Paul Bahn

‘The Celts – History and

Treasures of an

Ancient Civilization’ text by Daniele Vitali

‘Swanage and South

Dorset

Illustrated Guide

Book’ 1933/34

‘Britain BC’ by Francis

Pryor

‘Seahenge’ by Francis

Pryor

‘The Practical

Archaeologist’

by Jane

McIntosh

‘Coins of the England

and the

United

Kingdom’ by Spink

‘The Coins of Great

Britain and

Ireland’ by

Thorburn & Grueber (1905)

BBC

– DVD production ‘In

Search

of Myths

and Heroes’ presented by Michael Wood